-40%

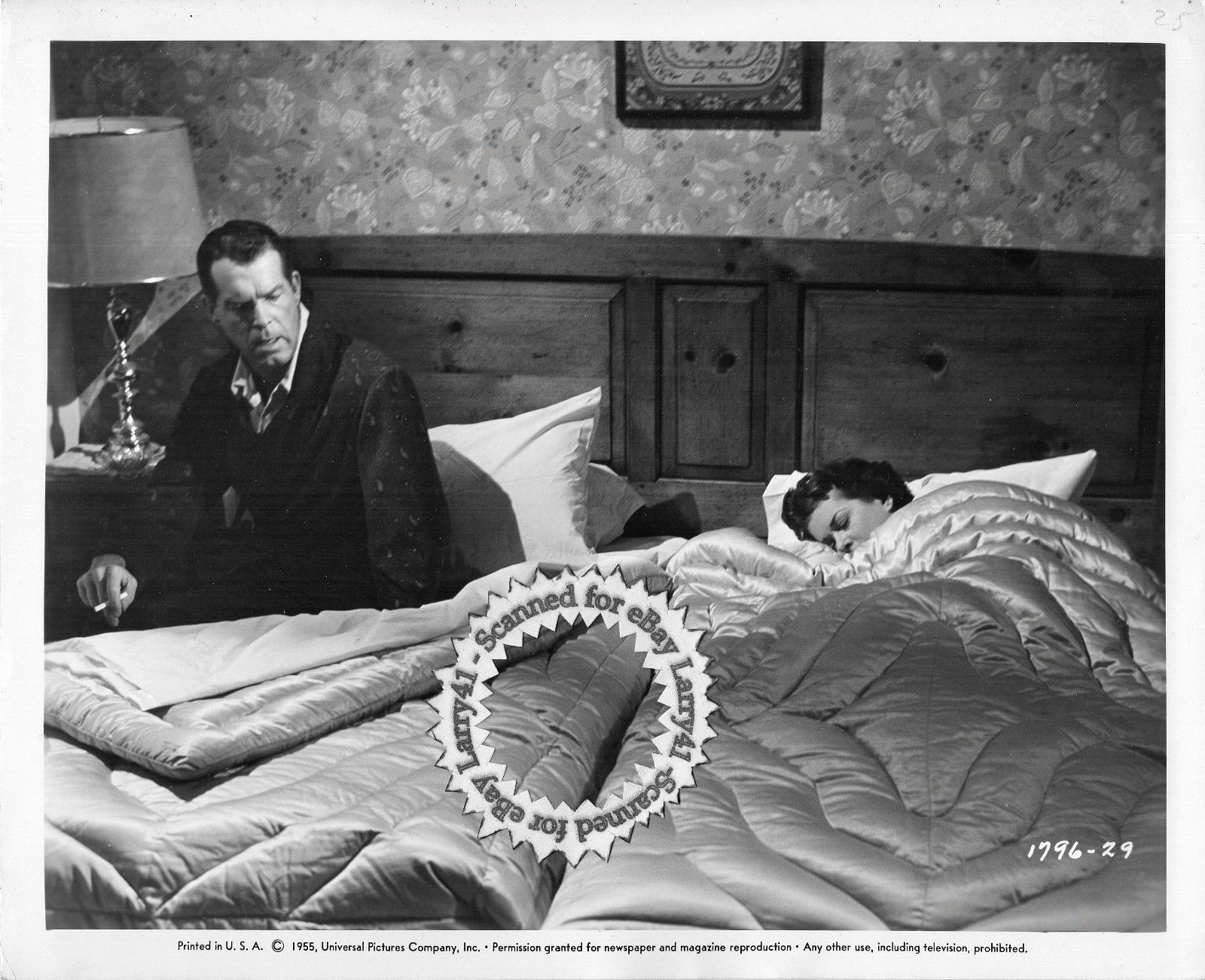

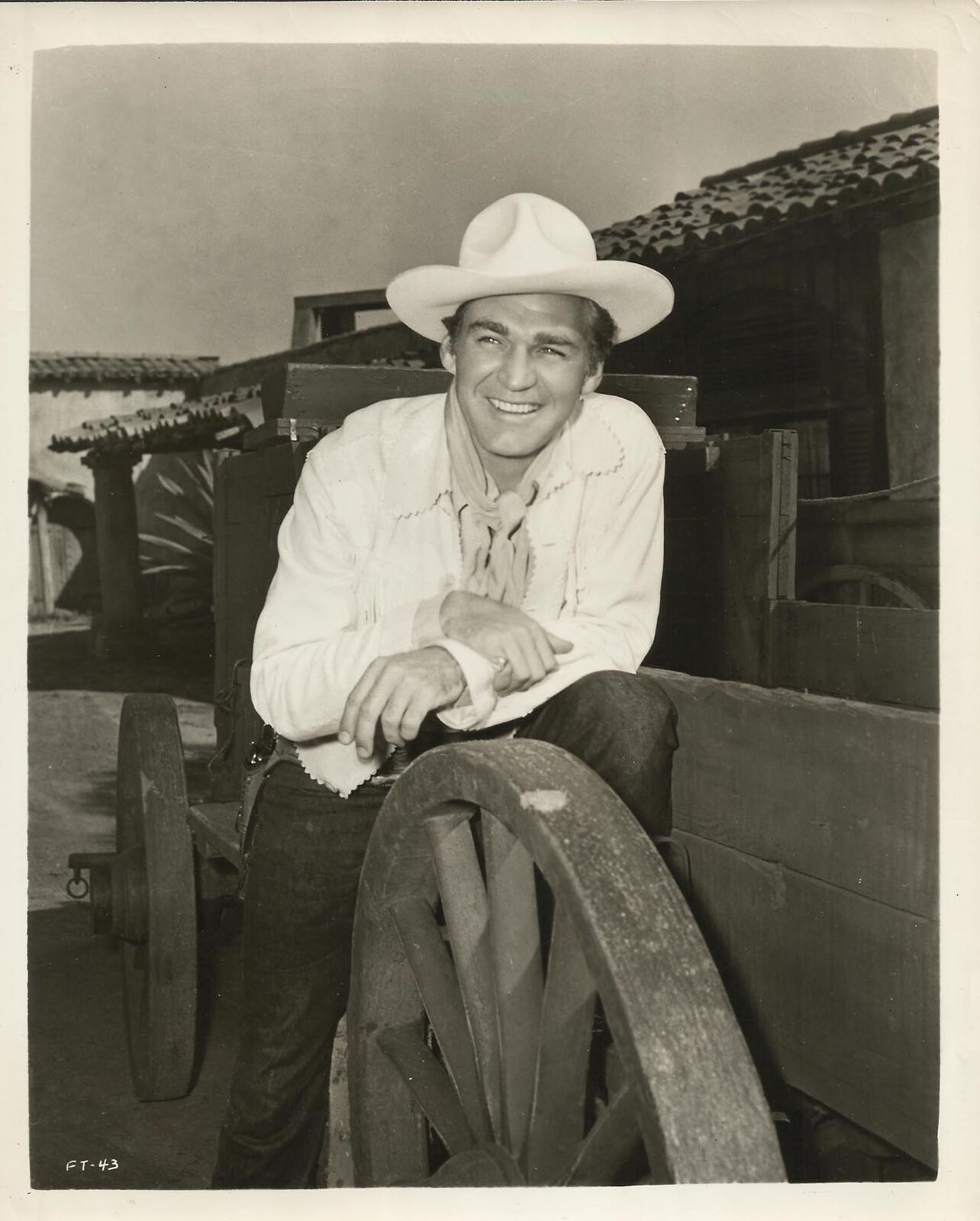

Douglas Sirk Fred MacMurray Joan Bennett still THERE’S ALWAYS TOMORROW 1956SNIPE

$ 5.28

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

(This looks MUCH better than this pictures above. The circle with the words, “scanned for eBay, Larry41” does not appear on the actual photograph. I just placed them on this listing to protect this high quality image from being bootlegged.)Douglas Sirk, Fred MacMurray, Joan Bennett still THERE’S ALWAYS TOMORROW 1956 +SNIPE! vintage original photograph

The circle with the words, “scanned for eBay, Larry41” does not appear on the actual photograph. I just placed it on this listing to protect this high quality image from being bootlegged. This would look great framed on display in your home theater or to add to your portfolio or scrapbook! A worthy investment for gift giving too!

PLEASE BE PATIENT WHILE ALL PICTURES LOAD

After checking out this item please look at my other unique silent motion picture memorabilia and Hollywood film collectibles! SHIPPING COST CAN BE CUT WHEN SHIPING MULTIPLE ITEMS TOGETHER AND SAVE $

See a gallery of pictures of my other auctions

HERE!

This photograph is a real photo chemical created picture (vintage, from the Hollywood studio release) and not a copy or reproduction.

DESCRIPTION:

Douglas Sirk is renowned for injecting his subversive criticism of American society of the fifties in his glossy and glamorous melodramas. What made this palatable to the public, who flocked in droves, was the fact that the families involved were showbiz families ("Imitation of Life"), filthy rich oil magnates ("Written in the Wind") or highly idealized to the point of caricature ("All that Heaven Allows", "Magnificent Obsession"), far from the average movie goers own social milieu. And of course up there on the screen were the glamorous stars, Rock Hudson, Lana Turner, Lauren Bacall, Dorothy Malone, etc. Movie fans will recall the aforementioned movies when the topic of Sirk's movies arises. It is highly unlikely that "There's Always Tomorrow" will get a mention. "There's Always Tomorrow" has barely any gloss or glamour. The social criticism is completely without disguise. The family in question is one that the vast majority of movie goers could very easily identify with. Its stars (Fred MacMurray and a not so young Barbara Stanwyk) are not glamorous. While audiences left the cinema entranced by the glorious melodrama of "Imitation of Life" and "Written on the Wind", they would have left "There's Always Tomorrow" feeling a lot less secure about their own lives, since it's a film that touches on a fair amount of "dangerous" territory, calling into question the very foundations of the American family. Douglas Sirk's sense of irony has never been sharper. The title brims with optimism and the film opens with the script, "Once Upon a Time in Sunny California". But what unfolds is a bleak, pessimistic depiction of middle class family life. While Sirk's films have often been branded "woman's pictures", "There's Always Tomorrow" is indeed very much a man's picture. It takes a hard and deep look at the role of the male breadwinner and the picture it comes up with is not a pretty one. What we are shown is a man who when young, courted the prettiest girl, married, had children and worked hard to build up a successful business. He is now middle aged and having achieved it all, begins to feel himself taken for granted by his wife and children. His needs are completely neglected. His wife has little interest in him sexually being totally wrapped up in fulfilling the unending needs of their self centered ungrateful children. It's a scenario all too familiar to millions of men. Fred MacMurrays's Clifford Groves has become a robot similar to the one his successful toy manufacturer has created. No wonder that Norma Vale's (Stanwyk) reappearance in his life presents an opportunity to regain his lost dreams. She's an independent career woman, who sees his situation as somewhat idyllic from the outside. But with the usual intelligence of a Stanwyk character, she has no illusions as to a possible future with him. Despite the brief and obligatory conciliatory ending, Clifford Groves' future does not bode well. It should come as no surprise that the film was not well received at the box office. "There's Always Tomorrow" has many of the hallmarks of Sirk's craftsmanship. The studio refused to grant him his request for the film to be shot in color, despite having provided Universal with some of its highest grossing pictures of the decade. At least his demand for his favorite cameraman Russell Metty was granted. Metty as always, was the perfect partner in realising Sirk's vision. His interior filming in particular is a lesson in cinematography. He had a penchant for shooting characters behind banisters, framed in mirrors and caged behind fences to enhance the sense of their being trapped. MacMurray and Stanwyk are constantly gliding through dark shadow and bright light reflecting the inherent brightness and darkness in their lives. At this point of writing "There's Always Tomorrow" has not been released in any format and rarely gets a showing on television. It's a gross injustice to an extremely important director and a wonderfully made, moving piece of cinema.

CONDITION:

This still is in Near MINT condition (with only minor bumps and tiny faint crease marks in the border area). I doubt there is a better condition still on this title anywhere! Finally, this is a vintage original. (This is NOT a cheap digital dupe, a re-release or copy, it is a real vintage photograph made the year of the release of the film.) It is worth more than -25 but since I have recently acquired two huge collections from life-long movie buffs who collected for decades… I need to offer these choice items for sale on a first come, first service basis to the highest bidder.

SHIPPING:

Domestic shipping would be FIRST CLASS and well packed in plastic, with several layers of cardboard support/protection and delivery tracking. International shipping depends on the location, and the package would weigh close to three quarters of a pound with even more extra ridge packing.

PAYMENTS:

Please pay PayPal! All of my items are unconditionally guaranteed. E-mail me with any questions you may have. This is Larry41, wishing you great movie memories and good luck…

BACKGROUND:

Most melodramas of the 1950s, including those made by the master of the genre, Douglas Sirk, address the experience of women: They suffer at the hands of men, their children, fate. But Sirk's 1956 There's Always Tomorrow is that rare melodrama that focuses on the world of men, specifically the plight of Fred MacMurray's Clifford Groves, a dutiful husband and family man. The film begins with a title card reading "Once upon a time, in sunny California." But the opening shot shows people hustling through torrential rains on their way to work, wielding their umbrellas like shields, a clear visual metaphor for the ways life doesn't always meet our expectations. And then we meet Clifford. He runs a thriving Southern California toy company, treating his employees fairly and with respect -- he's the prototypical decent guy, the kind of "good man" any woman would feel lucky to find. But when he goes home at night, his wife, Marion (Joan Bennett), barely has time for him, she's so caught up in the lives of their three children - they rule the household with their petty needs and demands. It's her birthday, and he's purchased tickets to a show, hoping the two of them might spend a rare evening alone together. But she waves him away -- their younger daughter has an all-important dance recital that night - and so Clifford retreats to the kitchen, where he sits alone, eating a meal the maid has prepared for him. The doorbell rings: Enter Barbara Stanwyck's Norma Vale, one of Clifford's former employees. She's now a successful clothing designer in New York, but she's come to California on business. She remembers Clifford fondly - perhaps morethan fondly - and just wants to say hello. Clifford is energized by this bright, vital woman who, unlike his wife, clearly takes an interest in him. The unhappy husband - like the unhappy wife in so many other melodramas -- begins to wonder: Might this new person bring him happiness? Plenty of films noir and '50s westerns examine the pressures and insecurities suffered by men in postwar America. But There's Always Tomorrow used melodrama to explore that experience. Sirk apparently recognized that it wasn't just women who worked hard to keep the families of 1950s America secure and well-fed. The German-born director, who had fled his home country for the United States in the late 1930s, was enough of an outsider to see this particular problem clearly. There's Always Tomorrow was based on a novel written by Ursula Parrott; an earlier film version, from 1934, starred Frank Morgan and Binnie Barnes. But Sirk, with the help of his superb cinematographer Russell Metty, adapted the problems of the lead character to the current times. The picture bears many of Sirk's stylistic trademarks, including shots framed through stair banisters or slatted partitions, to reinforce the idea that the characters are prisoners of the lives they've created for themselves. But there's more to There's Always Tomorrow than those easily recognizable Sirk visuals. The picture is emotionally rich and ultimately devastating; melodrama, when done right as it is here, is anything but heavy-handed. And yet Sirk himself seems to have underestimated the film. In Sirk on Sirk,> he told Jon Halliday that MacMurray's character "...is like a nave American boy who never grows up. And then Stanwyck comes back from his past. But she doesn't find a grown man. She leaves." But as Christopher Sharrett points out in an essay on There's Always Tomorrow in Cineaste magazine, "Sirk must have misremembered the film, since his prcis hardly speaks to its central themes, which, together with his usual craftsmanship, makes it one of his greatest, most fully-realized accomplishments. It has little to do with infantile regression-unless we look at the portrayal of children and the family. It is more accurately termed Sirk's most biting portrayal of suburban family life in the Fifties." Sharrett is right in his assessment of the movie's subtler qualities. Fortunately, in another interview, with Michael Stern, Sirk expanded on his reading of the film: "I think [There's Always Tomorrow] is a very sad picture because here is the American man dominated not by his wife so much as by the rules of society. She is as miserable as he, only she doesn't even know it! He can't escape. He can't make up his mind. He is the American man remaining a child. He is a producer of toys; still playing with toys. Then, his youth comes back. Knocks right on his door. And at the end, of course, he walks to the window and there is the plane flying away. It is his youth, his happiness." It's telling that Clifford's one chance at happiness should be played by Barbara Stanwyck. Stanwyck and MacMurray were one of cinema's inspired pairings, complementing each other perfectly in Double Indemnity (1944) and Remember the Night (1940), as well as There's Always Tomorrow. Here, Stanwyck's matter-of-factness as a businesswoman is balanced by her clear affection for her former boss; she even has romantic feelings for him, though she's not sure that she should act upon them. MacMurray's Clifford, on the other hand, is more malleable: If Stanwyck's Norma were to initiate an affair, he'd go with it - he yearns for attention and affection, and she seems poised to give it to him. Still, he feels more comfortable fulfilling his duty as a good husband. He tries to tell his wife all about his platonic friendship with Norma, to make it clear he has nothing to hide. He's weaker than Norma is, but he's also more susceptible to heartbreak and disappointment, as the picture's ending - seemingly ambiguous but wrenching -- makes clear. Sirk had actually planned another ending for There's Always Tomorrow: He wanted to show one of the toys manufactured by Clifford's company, a mechanical robot, walking toward the camera until it falls off a table. "The camera pans down, whoom! And there's the robot, on the floor, spinning, rmmm, rhmm, rhhmm ... rhhmmm, slowly spinning to a halt," Sirk explained to Stern. "The End. That is complete hopelessness. This toy is all the poor man has invented in his life. It is a symbol of himself, an automaton, broken." The ending Sirk ultimately chose is more subtle, and better for it. But it's a melodramatic conclusion, not a tragic one, and Sirk understood the difference - even as he understood how to satisfy an audience. As he said to Stern, "In tragedy the life always ends. By being dead, the hero is at the same time rescued from life's troubles. In melodrama, he lives on - in an unhappy happy end."